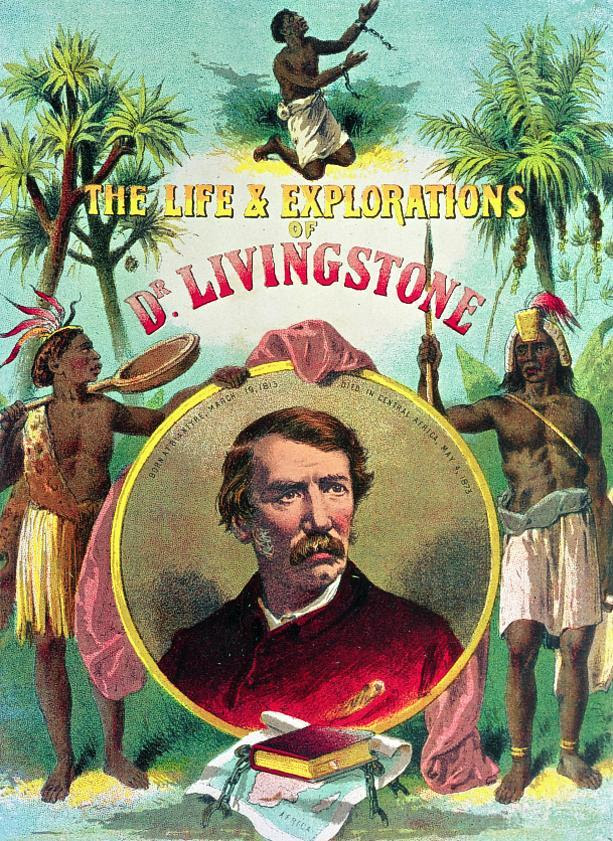

“Doctor Livingstone, I presume,” stated New York Herald reporter Henry Stanley on November 10, 1871, as he met David Livingstone on the banks of Africa’s Lake Tanganyika.

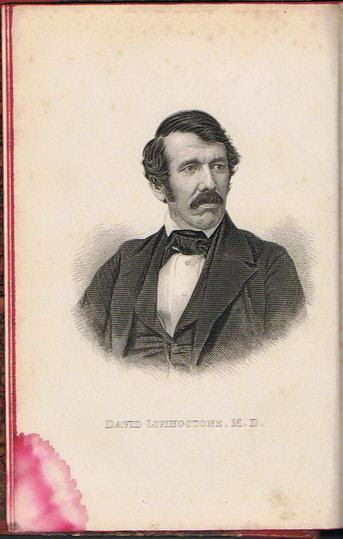

Dr. Livingstone was the internationally renowned missionary who had discovered the Zambezi River, Victoria Falls, and searched for the source of the Nile.

He had not been heard from in years and was rumored to have died.

Stanley, a skeptic, was sent from America to find him and write a story.

David Livingstone had been raised in the Church of Scotland, then the Congregational Church, and committed his life to Christ to become a medical missionary to China.

When the medical school required him to learn Latin, David Livingstone met a local Irish Catholic to tutor him, Daniel Gallagher, who later became a priest and founded St. Simon’s Church in Glasgow.

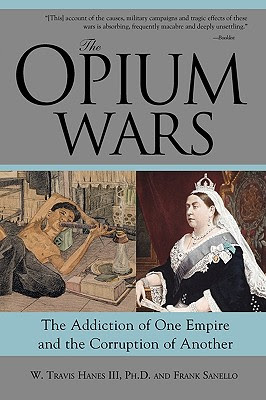

David Livingstone’s plans changed when the Opium Wars broke out in China.

Livingstone was convinced by Missionary Robert Moffat to go to South Africa where there was “the smoke of a thousand villages, where no missionary had ever been.”

In his journal, David Livingstone wrote:

“I place no value on anything I have or may possess, except in relation to the kingdom of Christ.

If anything will advance the interests of the kingdom, it shall be given away or kept, only as by giving or keeping it I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all my hopes in time and eternity.”

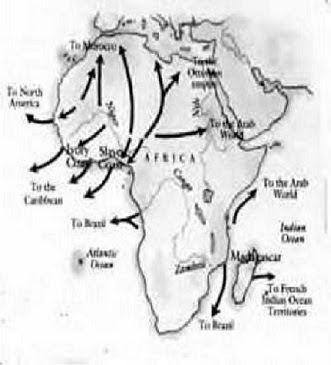

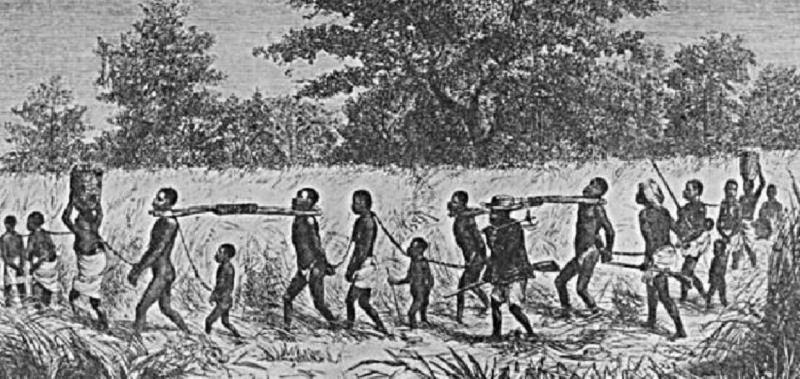

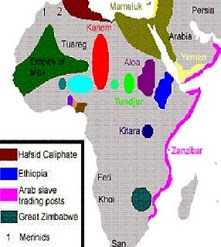

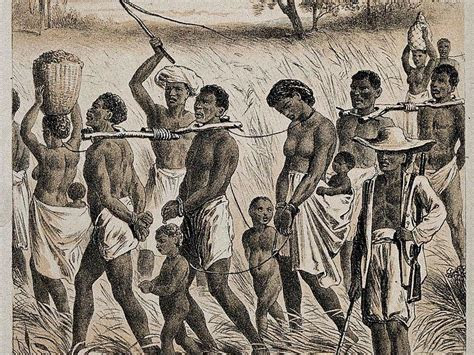

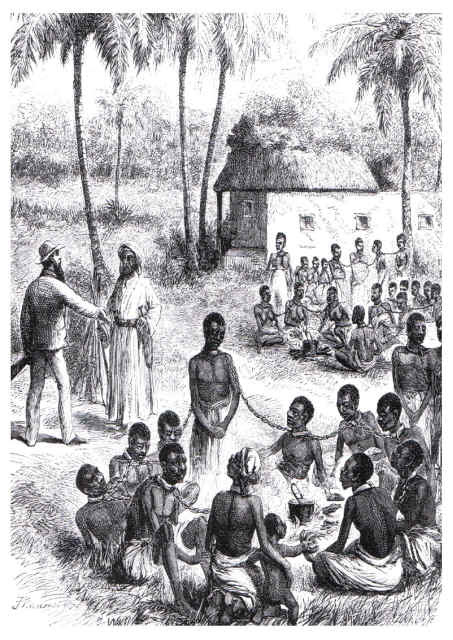

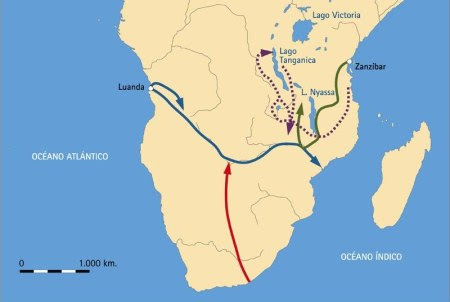

Traveling 29,000 miles back and forth across Africa, David Livingstone was horrified by the Arab Muslim slave trade.

His letters, books, and journals stirred up a public outcry to abolish slavery.

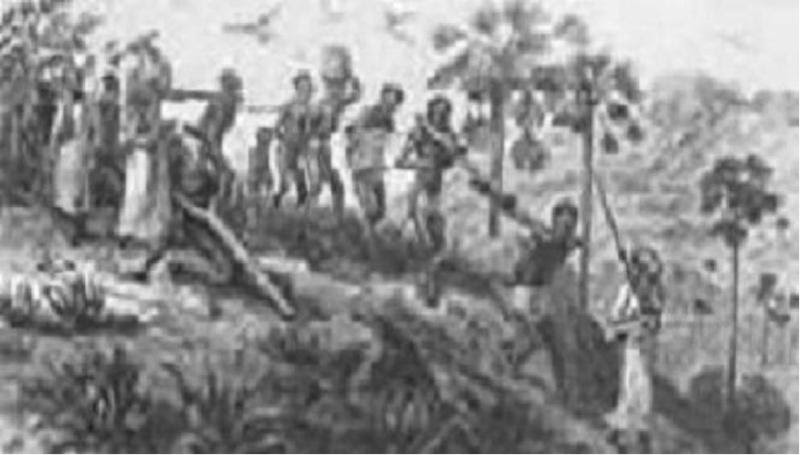

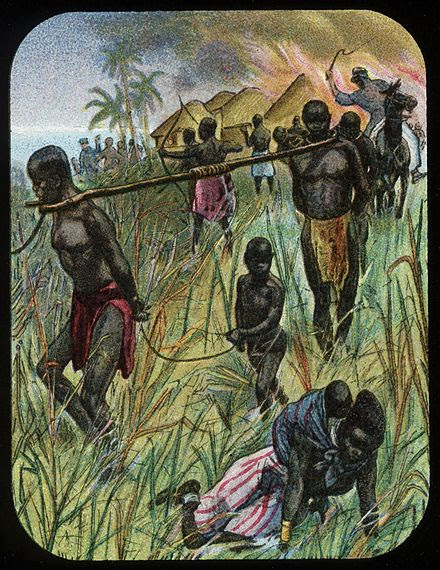

Livingstone often passed caravans of 1,000 slaves tied together with neck yokes or leg irons, marching single file 500 miles down to the sea carrying ivory and heavy loads.

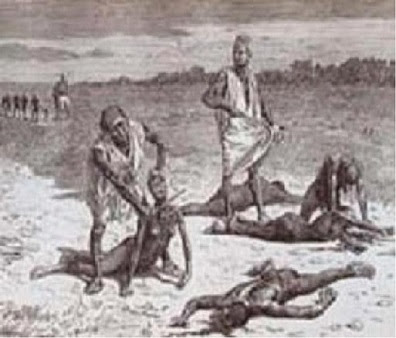

Slaves who complained were speared and left to die, resulting in slave caravans being traced by vultures and hyenas feasting on corpses.

David Livingstone recorded in his journal:

“To overdraw its evils is a simple impossibility …

We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead …

We came upon a man dead from starvation …

… We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path.

Onlookers said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer …”

He added:

“The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves.”

Livingstone estimated that each year 80,000 died while being captured or forced to march from the African interior to the Arab Muslim slave markets of Zanzibar.

Describing the Muslim slave trade as “a monster brooding over Africa,” Livingstone once walked 120 miles near Lake Nyasa without seeing a single human being, as Arab slave traders had so depopulated the area.

In 1862, David Livingstone received a steam boat, but attempts to navigate the Ruvuma River failed due to the paddle wheels continually hitting bodies thrown in the river by slave traders.

He had hoped to open up “God’s Highway” to bring “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization” into Africa, and thereby put an end to the Arab Muslim slave trade, as he wrote to the editor of The New York Herald:

“And if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.”

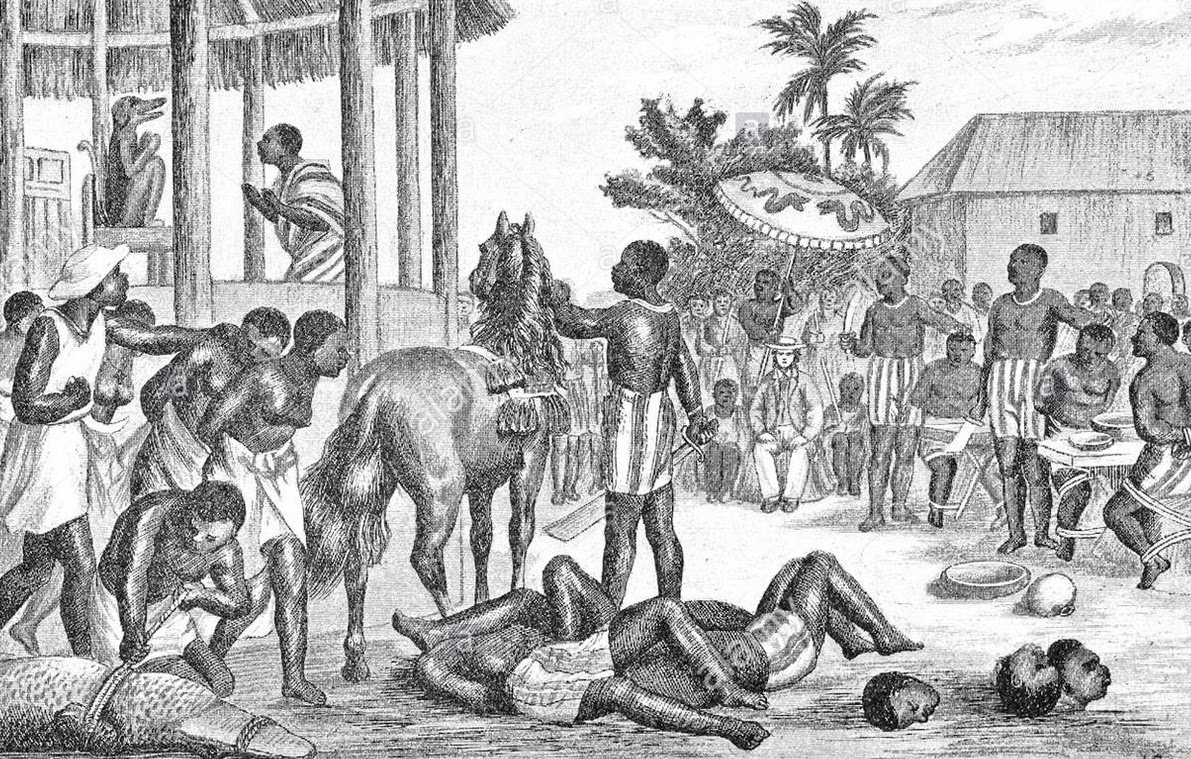

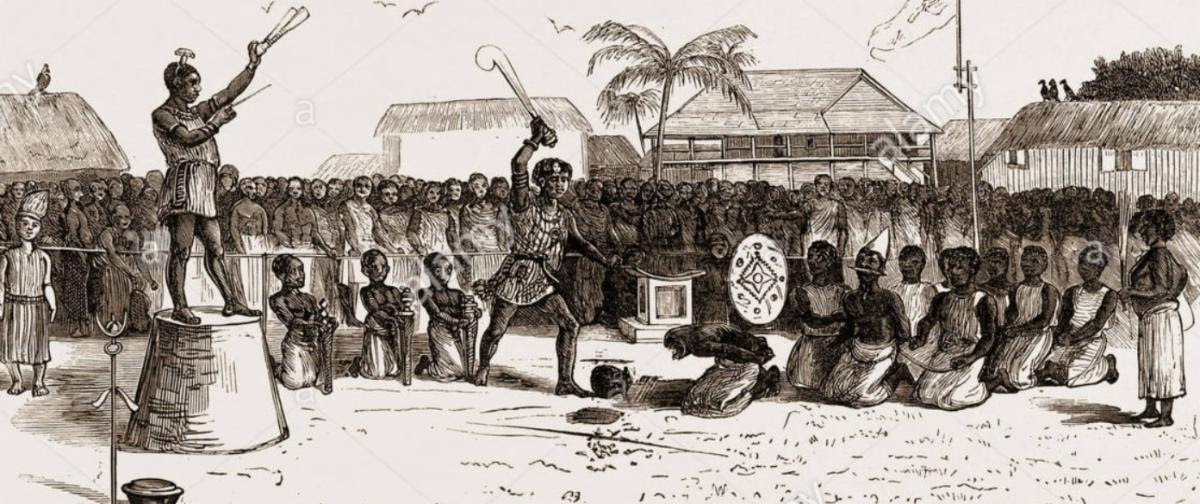

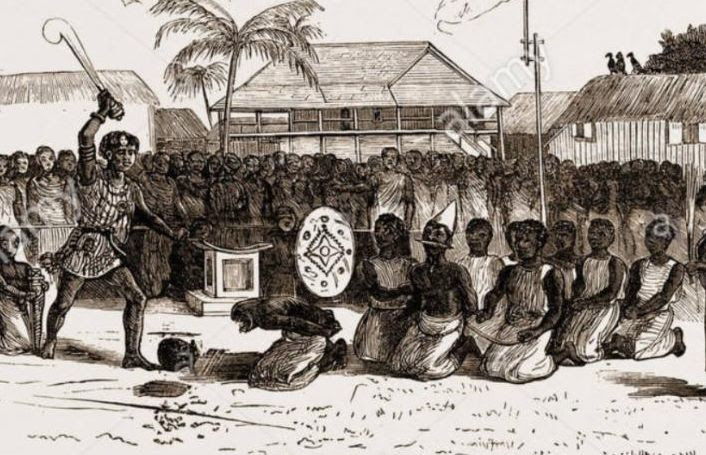

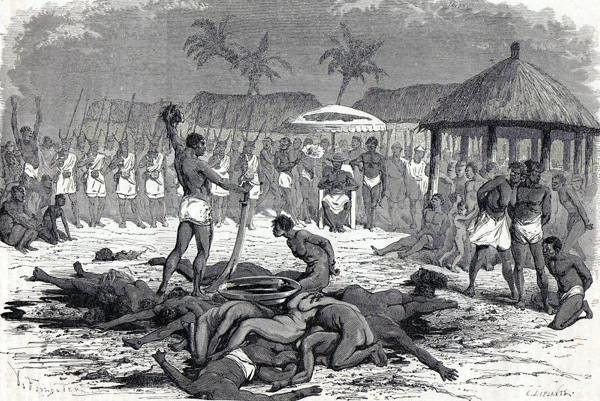

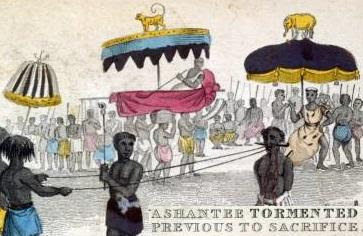

Another report was from Lord Baden-Powell’s 1896 book, The Downfall of Prempeh, who described the African king of the Ashanti tribe who used slaves for tribal sacrifice:

“Every tribe in the neighborhood of Ashanti lived in terror of its life from the king …

In England we scarcely realize the extent to which human sacrifice had been carried on in Ashanti …

… The name Kumassi means ‘the death-place.’

The town possessed no less than three places of execution; one, for private executions, was at the palace; a second, for public decapitations, was on the parade-ground; a third, for fetish sacrifices, was in the sacred village of Bantama.

Close to the parade-ground was the grove into which the remains of the victims were flung …

The ground here was found covered with skulls and bones of hundreds of victims …

… In these notes, be it remembered, we are only dealing with Kumassi but every king — and there were some half a dozen of them in the Ashanti empire — had powers of life and death over his subjects, and carried out his human sacrifices …

In fact, the ex-king of Bekwai was deposed on account of his over-indulgence in that form of amusement. Any great public function was seized on as an excuse for human sacrifices.

… There was the annual ‘yam custom,’ or harvest festival, at which large numbers of victims were often offered to the gods.

Then the king went every quarter to pay his devotions to the shades of his ancestors at Bantama, and this demanded the deaths of twenty men over the great bowl on each occasion.

… On the death of any great personage, two of the household slaves were at once killed on the threshold of the door, in order to attend their master immediately in his new life, and his grave was afterwards lined with the bodes of more slaves who were to form his retinue in the spirit world.

It was though all the better if, during the burial, one of the attendant mourners could be stunned by a club, and dropped, still breathing, into the grave before it was filled in …

… This custom of sacrifice at funerals was called ‘washing the grave.’

On the death of a king the custom of washing the grave involved enormous sacrifices.

Then sacrifices were also made to propitiate the gods when war was about to be entered upon or other trouble was impending.

Victims were also killed to deter an enemy from approaching the capital; sometimes they were impaled and set up on the path, with their hand pointing to the enemy and bidding him to retire.

… At other times the victim was beheaded and the head replaced looking in the wrong direction; or he was buried alive in the pathway, standing upright, with only his head above ground, to remain thus until starvation or — what was infinitely worse — the ants made an end of him.

Then there was a death penalty for the infraction of various laws.

For instance, anybody who found a nugget of gold and who did not send it at once to the king was liable to decapitation; so also was anybody who picked up anything of value lying on the parade-ground, or who sat in the shade of the fetish tree …

… In no part of the world does slavery appear to be more detestable than in Ashanti.

Slaves other than those obtained by raids into neighbors’ territory, have here to be smuggled through the various ‘spheres,’ French, German, and English, which are beginning to hem the country in on every side.

… The climate they are brought to is a sickly one for men bred up-country.

They are not required currency, since gold-dust is the medium here.

Nor are they required to any considerable extent as laborers, since the Ashanti lives merely on vegetables, which in this country want little or no cultivation.

… And yet there is a strong demand for slaves. They are wanted for human sacrifice.

Stop human sacrifice, and you deal a fatal blow to the slave trade, which you render raiding an unprofitable game.”

Sadly, slavery of Africans still continues in Islamic dominated areas of Africa, and political groups that demand reparations for past slavery are strangely silent about modern-day slavery.

Fredrick Ngugi wrote May 5, 2017, Face2FaceAfrica.com:

“It may be more than two centuries since the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade ended, but slavery is still very much alive in many African countries as well as much of the ancient world.

Other varied forms of slavery still exist across the continent, including domestic service, debt bondage, military slavery, slaves of sacrifice, local slave trade, and more.

Here are the top five African countries where slavery is still rampant: Mauritania; Sudan; Libya; Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula; South Africa.”

Reaching the headwaters of the Congo at Lualaba River in 1871, which he mistakenly thought to be the Nile, Livingstone recorded that at Nyangwe he saw Arab Muslim slave traders massacre nearly 400 Africans.

Disheartened, he went back to Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika, where, after years of the world not hearing from him, The New York Herald reporter Henry Stanley found him.

Henry Stanley described the famous old missionary:

“Here is a man who is manifestly sustained as well as guided by influences from Heaven.

The Holy Spirit dwells in him. God speaks through him.

The heroism, the nobility, the pure and stainless enthusiasm as the root of his life come, beyond question, from Christ.

There must, therefore, be a Christ;-and it is worth while to have such a Helper and Redeemer as this Christ undoubtedly is, and as He here reveals Himself to this wonderful disciple.”

David Livingstone, ever the explorer, stated:

“I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward.”

Once he was attacked by a lion.

Livingstone wrote that it:

“… caught me by the shoulder as he sprang, and we both came to the ground together.

… Growling horribly close to my ear, he shook me as a terrier does a rat.”

Livingstone was so loved by Africans that when they found him dead in 1873 near Lake Bangweulu, kneeling beside his bed after suffering from malaria, they buried his heart in Africa.

His body was sent, packed in salt, back to England to be buried in Westminster Abbey.

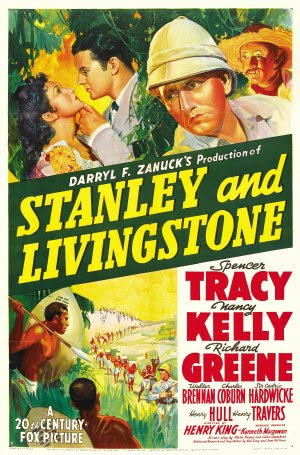

Monuments around the world are dedicated to the memory of David Livingstone, as well as movies and documentaries, including the 1939 film Stanley and Livingstone, starring Spencer Tracy.

In his Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, 1857, Dr. David Livingstone revealed what motivated him:

“The perfect fullness with which the pardon of all our guilt is offered in God’s Book, drew forth feelings of affectionate love to Him who bought us with His blood …

A sense of deep obligation to Him for His mercy has influenced … my conduct ever since.”

—